All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Qualitative Study of Migrant Family Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain

Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic stemming from the global contagion of the respiratory virus first identified in 2019, now ongoing for four years, impacted the world in different ways that are important to understand for its short and long-term mental health risks. This study aims to examine the experiences of migrant families in Spain as a vulnerable cluster, identifying the characteristics under which they had to adapt in Spain, affecting their psychological well-being.

Methods

This research used a qualitative research design to explore the experiences of the families during the pandemic, during closures, and after the quarantine was lifted in Spain. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a child and a parent of 17 migrant families.

Results

The key themes that emerged from the interviews with this sample’s experiences regarding their life during the pandemic were social isolation, routine interruption, economic difficulties, and bureaucratic obstacles that ensued from public health restrictions, the COVID-19 pandemic virus, and related conditions during the years 2020 to 2022. This indicated potential risks to the families’ psychological well-being and their mental health by increasing stress and removing or reducing access to social support systems within the neighborhood they settled in postmigration, limiting the study due to the unique set of characteristics this sample faced.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic added to existing challenges relating to local migration, increasing risk factors for migrant’s mental health, removing protective factors they sought in migrating to Spain, and complicating their post-migration adaptation by influencing their legal paperwork applications, children's schooling, employment, housing, language acquisition, and cultural integration.

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, stemming from the global contagion of the respiratory virus identified first in 2019 in China, impacted the world in different ways that are important to study [1]. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mental health have been a subject of great concern due to multiple aspects of the experience that, in other conditions, have been identified as risk factors to people’s psychological well-being, such as a higher death toll, seclusion, and an ensuing economic downturn. Of increased concern during times of national and international crises are vulnerable populations, who not only suffer the same difficulties as the general population but also face additional challenges unique to their group. This is why this paper examines the experience of migrants in Spain, focusing on the vulnerable community in the migrant-populated neighborhood of Sant Roc, Catalonia.”

While other studies have examined the impact on adults and children individually, this study aimed to examine the impact on both as the family unit, as health restrictions demanded families quarantine together, increasing the amount of time they shared [2, 3]. Children and parents’ mental health has been identified to be closely linked, particularly migrant children’s well-being is linked to parents’ mental health [4]; during the quarantine period, this was likely enhanced by the increased time spent together and decreased time in other community spaces where children received support from other relationships.

Although families with school-aged children were not among the demographic who have stood out in other studies as experiencing the more severe or alarming physical symptoms due to the COVID-19 virus [5], the concern for their mental health does not stem from the physical experience of the virus but rather due to other aspects of the pandemic experience in Spain such as prolonged quarantines, social isolation, fulfilling school duties at home, and the economic difficulties their families experienced. Apart from the medical conditions caused by the pandemic, the economic, social, and psychological impacts were similarly difficult for all people to manage. This study aims to investigate the particular experiences of migrant families under these circumstances, who experienced the combined difficulties of their immigrant status, postmigration adaptation, and the pandemic as simultaneous challenges.

1.1. Mental Health Impact of the Pandemic

Four years after the beginning of the pandemic, there is now a clearer understanding of its psychological impact. The overwhelming evidence demonstrates that pandemics are precursors to mental health decline in the general population [6]. Research indicates that the harmful effects on mental health were not necessarily tied to or confined by how close individuals were to an infectious outbreak [7]. The general population has experienced an increase in anxiety and depression as a result of the pandemic and its surrounding characteristics, which are important to identify [2]. These disturbances are closely linked to interruptions in activities that provide meaning, purpose, socialization, and income, affecting people's sense of self-worth, life satisfaction, sense of belonging, structure, life goals, health, and overall well-being, which are critical psychological markers. Additionally, the uncertainty surrounding evolving public health measures has further increased psychological distress [8]. While social distancing and quarantining provided clear health benefits during the pandemic, they also raised concerns about mental health risk factors. Increased negative emotions and psychological distress can weaken the immune response, potentially leading to further health issues [9]. Unfortunately, the availability of mental health workers to address this crisis has been far too limited [10].

In terms of children’s mental health, the developmental vulnerability of young people made them particularly prone to mental health issues during the pandemic. Early studies identified that individuals in these age groups were especially susceptible to developing mental health symptoms due to ongoing stressors such as school and university closures, loss of routine and social connections, and diminished economic prospects [2]. With schools, daycare centers, and other childcare options becoming unavailable, the disruption of routines, which are especially important for children with mental health issues, became a significant concern [9]. Additionally, the time children spent online increased due to social isolation, a troubling trend given the correlation between increased screen time and a rise in mental and behavioral problems [6]. The disruption of routines, particularly family routines, has been linked to the emergence of mood disorders and is crucial to children’s psychosocial development [11].

Regarding migrant mental health specifically, studies quickly emerged as concerns about the successful adaptation process became increasingly relevant for governments. Metanalyses and scoping reviews have identified several common experiences as risk factors for migrants' mental health [12]. Migrants and refugees frequently face multiple challenges that can negatively impact their mental health, including unstable housing, living in socially isolated and impoverished communities, prolonged uncertainty about their legal status and future prospects, and significant barriers to workforce entry and financial security [7]. During the pandemic, reviews highlighted that poor living conditions, job loss, and the inability to meet basic needs contributed to a rise in depressive and anxiety disorders, as well as substance abuse among migrants [13]. Additionally, a survey (Health Behavior in School-aged Children - HBSC) found that 20% of adolescents in Europe are of migrant background, with migrant children particularly prone to mental health issues a year after the pandemic [14].

1.2. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain

In the first two decades of the 21st century, Spain experienced two significant surges of international migration. The first occurred from the early 2000s until the Great Recession of 2008, marking Spain's transformation into a key immigration destination, where migration increased the population more significantly than previous growth trends predicted. The second surge began with the economic recovery in 2014 [15] and continued until the COVID-19 pandemic forced border closures in March 2020. Although less discussed, this second wave demonstrated the resilience of Spain's demographic system and the persistence of established migratory patterns, particularly between Spain and Latin America. Both migration booms were abruptly halted by crises, first by the economic downturn of 2008 and then by the pandemic [16]. These global crises had different impacts on migration trends and demographics. The pandemic strained the health and social systems, as well as the statistical systems that track migration. Despite a history of detailed migration records, Spain faced challenges such as delayed data publication and uncertainties in recording internal and temporary migration. These statistical shortcomings complicated the analysis of migration trends during the pandemic [17].

The pandemic played out slightly differently for populations depending on the policies implemented by different governments and geographic characteristics. During the initial wave of COVID-19, 168 countries decided to close their borders to protect their populations from experiencing a contagion surge. However, for migrants, this interrupted resettlement efforts [18]. Spain was one of these nations; unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak rapidly escalated, making it the second epicenter in Europe after Italy, and led to a centralized response by the Ministry of Health, including a strict lockdown that halted most economic activities for weeks. Declaring a state of alert on March 14th, 2020, Spain temporarily centralized its decentralized health system under the Ministry of Health, focusing on centralizing the purchase of goods, resource allocation, and production management. This centralization lasted until the State of alert ended on June 21st, after which regional authorities gradually regained their healthcare responsibilities as the outbreak was brought under control [19]. The containment measures put in place at first included closing schools and businesses, obligatory facemasks, and home quarantine for the entire population except essential workers such as health and food workers. These were some of the strictest measures implemented around the world, seen only similarly in Italy. The measures were gradually relaxed in May 2020 and were finally lifted by June 20th. After this, people were asked to self-quarantine if they experienced symptoms, tested positive, or came in close contact with someone who tested positive for the virus [20]. Between 2020 and 2024, Spain has seen 120,000 deaths due to COVID-19 [21]. In 2021, levels of anxiety and depression in the overall Spanish population were seen to increase by 31.4% for the former and 31.9% for the latter [22].

For migrants specifically, the pandemic years were also complex. At the beginning of 2020, nearly 15% of Spain's population (7 million people) were foreign-born, with the largest immigrant groups from Morocco, Romania, and Colombia. It was also estimated that by the end of 2019, there were between 390,000 and 470,000 undocumented migrants, representing about 0.8% of Spain's total population. Migrants faced higher unemployment rates, with foreign workers experiencing a 25% unemployment rate by mid-2020, compared to 11% for nationals, and those most affected included women and young people under 25. This economic vulnerability exacerbated the risk of poverty, with 50% of foreign-born households being at risk. For many migrants, job loss further threatens their legal status and visa processing [23]. Those wishing to migrate during the pandemic faced particularly difficult conditions. The CEAR’s 2020 report registered concerning statistics: Spain accepted only 5.2% of asylum applications, significantly lower than the usual European average of 31%. This is concerning because one in fifty-five people die attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea [24].

Since migrants represent such a significant portion of the population, concerns about their experience of the pandemic and how the systems might have been unable to respond to their needs prompted studies all around Europe, such as Norway and Italy [25, 26]. In Spain, migrants who experienced isolation due to COVID-19, relied on substances to cope with the pandemic, and had preexisting chronic illnesses reported the highest levels of psychological distress in measurements of their mental health following the end of the pandemic [27]. Local studies have investigated the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic on different populations of migrants, such as women, men, or unaccompanied minors [28-30]. However, this study chose to focus on migrant families, gathering the experiences of related adults and children. Spain has focused many efforts on studying, advocating, and supporting unaccompanied minors; however, accompanied minors have not been the focus of much research. This study intends to fill an important gap, identifying the characteristics under which families had to adapt in Spain, affecting or supporting their psychological well-being.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

This article presents a subsection of the data from a study about the mental health and experiences of migrant families, particularly the data extracted from responses relating to their experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, which coincided with the study unexpectedly. This study interviewed 17 migrant families (N=34), one parent, and one child from each family. The families were from Morocco, Pakistan, Bolivia, Peru, China, and Honduras.

Families were selected and recruited through a convenience sampling method by reaching out to migrant families who attended the open center for non-formal education for migrants called the Ateneu Foundation of Sant Roc in the neighborhood of Badalona, located next to the city of Barcelona. This area was chosen because it is a common neighborhood for migrants entering Spain through Catalonia to settle in due to its government-funded housing. Many migrants enter Europe through Spain and enter the latter, specifically through Catalonia [31]. Thus, this was deemed an important sample of the trajectory into the continent undertaken by many migrants. The foundation has settled into the neighborhood for 60 years and has become well-known by word of mouth as the primary place migrant families can find support in navigating the process of learning the local languages (Spanish and Catalan), supporting children transitioning into the local schooling system, and navigating their visas and other paperwork they file with the government. This center was selected as the place to connect with highly vulnerable migrant families from multiple origins, representing the multi-origin nature of migration in Catalonia.

Families from any origin were invited to participate, with a parent and a child from each family where the parent was a first-generation migrant. The children interviewed could be first or second-generation. However, many did not qualify into either category but rather what has recently begun to be referred to as 1.5 generation, defined as children who migrate when they were young and who grew up in the country of destination.

Migrants were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews about their migrant experience on the premises of the foundation in between their activities at the center. The foundation offered attendants the opportunity to participate in the study, and those who agreed were scheduled to be interviewed to protect their private data and not disseminate it without their approval. Parents were interviewed first to sign their consent forms and those for their children. Their children were then interviewed and asked to sign an assent form. This study received ethical approval from the Comisión de Ética en la Experimentación Animal y Humana (Ethics Committee on Animal and Human Experimentation) from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (CEEAH 5523).

2.2. Design

This study used a thematic analysis of the data gathered through a qualitative research design consisting of in-person, one-on-one interviews with a parent and a child from migrant families. The researcher asked open-ended questions from an interview guide designed for this study based on a previous scoping review that identified the primary concerns of migrant children’s mental health, among which many depended on their parents’ education, career, communication skills, and mental health. Thus, this study design included both parents and children to gain a more holistic insight into accompanied children’s postmigration adaptation [12]. The study coincided with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, delaying the intended start of the interviews in 2020 to 2021. This study deemed in-person interviews particularly important, as many migrant women from countries with low female literacy rates, such as Morocco or those with young children, cannot participate in written surveys—an approach used in other studies on the mental health of migrants in Spain [32]. The interviews began by collecting demographic data, then about their migration journey, followed by their family life and routine postmigration, and finally about their emotional experience relating to their mental health, allowing space for participants to expand on the subjects they deemed important and inquiring with follow-up questions.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were recruited through their attendance at the Ateneu Foundation of Sant Roc. The interviews were conductedin the offices and classrooms of the foundation. In order to follow COVID-19 protocols, the interview was conducted with an open window, a desk in the middle to provide social distancing between the researcher and participant, and masks were kept on during the interview. Between each interview, the space was disinfected. The interviews lasted between 25 minutes and an hour and a half. They were conducted between 2021 and 2022 once quarantines were lifted in Barcelona, Spain.

At the beginning of each interview, the participant was read a summary description of the study. Then, they were informed of their right to terminate the interview at any point and leave and to remove their responses from the research database at any point. They were informed about the procedure to handle their data and guarantee anonymity and privacy. Once the initial brief was done, participants signed their consent. Then, they were informed that the interview was about to begin, and the final verbal consent was obtained before turning on the recording.

The researcher posed open-ended questions predetermined by the interview guide, and unplanned follow-up questions were asked for clarification or expanding their response to achieve a semi-structured interview. The interviewer followed the conversational flow of the interview to allow the participant to expand their narrative. At the end of the interview, participants were asked if they had any questions, and then the recording was turned off. The researcher reminded the participants of their right over their data and responses. Then, the researcher saved the audio file to a private cloud drive. Interviews were then transcribed with identifying information redacted. Interviews conducted in Spanish were then translated to English, reflecting the original grammatical and vocabulary choices equivalent to the language of the original interview.

2.4. Data Analysis

The transcriptions and audio files were analyzed with a manual thematic approach in six steps used by Smith, Larkin, and Flowers [33], given as follows:

2.4.1. Reading

Researchers familiarized themselves with the interviews by reading, rereading, and listening to the audio files.

2.4.4. Iteration

Researchers compared their individual findings and coding, performing several revisions to identify common codes and themes.

2.4.5. Narration

Researchers developed a cohesive narrative from the themes identified with example quotes for illustration.

2.4.6. Contextualization

The team interpreted the findings according to previous research and contextualized them within the literature.

The thematic analysis involves an interpretative process, starting with the categorization of data into broad themes, followed by a continued review to identify more specific themes. This study aimed to highlight the subjective lived experiences of migrants and how these experiences impacted them concerning their psychological well-being. Since the interpretative process can include biases by the researcher, the interviews were conducted by ASA (doctoral candidate), and the transcripts were then coded by the three authors separately (two PhD supervisors). The manually identified themes were compared to highlight and select the most important and recurring themes emerging from the analyses; this process of individual-to-group analysis of the data helped ensure intercoder reliability by selecting the relevant themes that all researchers agreed were relevant to the study.

3. RESULTS

After analyzing the responses obtained from the interviews, several themes emerged around the families’ experiences of their lives during the time of the pandemic, during closures, and after the quarantine was lifted in Spain. From these experiences emerged the stress and emotional difficulty experienced by the members of these families stemming from isolation, separation from significant social support, and departure from their sense of normalcy. Some of the participants expressed clearly the emotions associated with these experiences. Other participants did not label the emotion, but the meaning behind their statement can be deduced as a negative emotion. The translated quotes are included below.

3.1. Social Isolation

Since the pandemic’s concern early was on the rise in contagions overwhelming the healthcare system before the vaccine became available, the government’s priority was to reduce the number of cases by social distancing and quarantine within the home. This is why it is unsurprising that a distressing experience reported by participants was the loneliness of social isolation. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Do you have friends in the neighborhood?

“Yes, I have girls. We went running when I was young. But now life has changed with this (pandemic)” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

For adults, social isolation was reported from their friendships as well. Many migrant families expressed the importance of friendship in their country of destination, as they did not have the social support of family, who had remained in their country of origin, giving their friendships an increased importance, and thus an increased sense of grief at being unable to engage with them during the social distancing period. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Do you have friends in the neighborhood?

“Yes, like family. Yes, I have friends like sisters, when I am sick, or they are sick… like family, they call me every day to ask how I am, and I call them” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Technology allowed people to remain somewhat connected to their important relationships, whether they were in the same neighborhood or another country. Their phones allowed them to call and video chat. One of the participants further responded:

“Well, only with confinement with the pandemic, I don’t go because my mother, I don’t take my children because of my mother. I’m afraid if something happens” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

For socialization with older adults, such as older relatives, interactions had to be limited for their safety. After the initial state of alarm, households were allowed to interact with a limited number of other households. The state did not mandate that people refrain from visiting older relatives; rather, many made a personal decision to maintain their distance in order to protect them. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Have you felt lonely?

“Right now, yes” (Daughter, Bolivia, translated).

The interviews scheduled with some participants had to be rescheduled multiple times due to quarantines imposed after multiple contagions at their schools. For this child, after rescheduling several times, the interview was finally conducted over the phone while she quarantined at home. She expressed clearly, the sentiment of loneliness that she felt having to quarantine again. One of the participants further responded:

“First, my children were very upset because when we came here, it was in lockdown. They could not manage to go to school, and they were very depressed and dejected” (Mother, Pakistan).

For those who migrated in late 2019 or early 2020, their arrival was marked by the pandemic, making their initial settling process difficult and uncommon. Children were unable to attend school at first, and an already complex cultural, linguistic, and academic transition was further complicated. The isolation was particularly pronounced for those who had been unable to establish any social connections when the quarantine began.

3.1.1. Family Separation

Family separation was a subtheme of social isolation. Migrants reported members of their families, immediate or extended family members, lived in their country of origin. Due to geographic distances and government policies closing borders, they were cut off from their families for multiple years. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Do you go to Morocco often?

“Yes. Well, the last years of COVID, we did not go, but we go every year” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Many families reported regular visits to their country of origin as important to their family to remain connected with extended family and with their culture. They valued their children maintaining connection to their roots. The pandemic separated them from this extended family and culture. One of the participants responded to the following question as:Does your husband live with you?“ Yes, with me. Now he is sick. When he leaves for Pakistan. His father died. There he was when Corona. His ID ended there. He can’t come back yet” (Mother, Pakistan, translated)

For this family, the woman’s husband traveled to Pakistan, their country of origin, when his father died, and then the pandemic began, cutting off travel between Pakistan and Spain, where he got stuck for the initial state of alarm. During this period, his visa expired, and extended his stay while he was able to renovate the paperwork, allowing him to travel and rejoin his family. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

In the last months have you felt sad or anxious? Why so?

“Sad, yesterday I was sad. Because my great aunt died of COVID, I have three that have died, and I can’t get over it much. I lived moments with them. They were in Peru” (Daughter, Peru, translated).

Experiences of grief were increased due to contagions. Some families reported members catching the virus and even dying from it. They were unfortunately unable to grieve with their families, attend funerals, or visit the sick.

3.1.2. Family Coexistence

A notable subtheme related to social isolation was the relational impact of quarantine on the migrant households. In other words, the composition of the groups who shared quarantine within the same apartment or homestead. In this study, migrant families typically consisted of one or two adults with one or more children. Among these families, several had experienced separation or divorce. For instance, one family consisted of a woman and her child who shared a single room in an apartment with unrelated roommates, as this was the only affordable option available to them. Additionally, many of these families resided in social housing within challenging neighborhoods. The small apartments and lack of individual rooms or space meant if one family member tested positive, there was no place for them to quarantine, and the other members usually ended up testing positive, too.

These factors were crucial when examining the experience of home quarantine, as the living conditions and household composition significantly influenced the quality of life during extended periods of confinement. For some families, the conflictive dynamics of their family relations made the pandemic particularly difficult, contributing to multiplying experiences affecting their mental health. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Who lives in your house?

“My stepfather, and my mother and I... I miss Peru. I miss my father. Because since he is not with me here... A little sad because I separated from my father, I was very attached to my father. How do you get along with your stepfather? Terrible. It's just that, let's see, he's not like my father. I don't like him because sometimes he gets angry. He makes things really hard…We quarantined again because my stepfather tested positive. Before Christmas he caught COVID again” (Daughter, Peru, translated).

For this girl, the experience of having to stay home every time one of her family members tested positive for COVID-19 was difficult, as she highly disliked her home environment due to the conflictive relationship with her stepfather. She could not quarantine with her father instead because he lived in their country of origin, Peru, and during this time, she was unable to visit or see him.

3.2. Routine Interruption

An important theme that emerged from the interviews was the interruption of the families’ regular routines. For parents, this was regarding their job schedules due to a reduction in work hours or losing their employment. For children, the closings of schools and the Ateneu Foundation, where they spent the weekday afternoons. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

How did they do school during the pandemic? Online?

“No, they sent it by mail and that’s it. Sometimes they called, with a call and that’s it. Did you have to help? Yes, do homework with them, then take pictures, send them… it’s hard” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Particularly, the interruption of children’s routine of attending school was a complex interruption. Having to perform school activities from home required the participation of their parents to fulfill their class duties. Their parents had to extend hours caring for their children at home, unable to leave their children home alone to go to work, and additionally, they had to help them with schoolwork. The families in this sample had fewer resources, particularly technological resources such as computers, smartphones, and internet connections with which to continue their children’s education, widening the socioeconomic gap that public schools often manage to bridge. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Did they do online classes?

“Not this year. Last year yes, when the pandemic started. Yes. But this year only for example my son’s class was confined only one time. There only those 10 days he had class online but then normal class” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Even after the three-month quarantine in Catalonia was lifted, people were expected to resume social distancing at home if they tested positive for COVID-19. This resulted in multiple isolation periods during the years after the virus was first identified. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

What do you do after school?

“ I play a bit on the PlayStation, cellphone. Depends on the day. I come here [Ateneu Foundation] to have fun, we play something. Activities. Before I went to football, but I had to skip because of COVID. But I’ll sign back up then. When everything is fine” (Son, Morocco/Pakistan, translated).

For children, recreation is an important part of their development and socialization. The activities they were often relegated to alone in the home were on their technological devices. Several children expressed spending long hours playing on their phones or game consoles, and several parents were concerned about this way of spending their time. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

What does your family do when you’re on vacation from school?

“The last time I don’t know because me, I left, I had COVID and I stayed in my room and when I was done had just left, I didn’t know what they had done during the organized activities (Ateneu Foundation)” (Daughter, Pakistan, translated).

The migrant families interviewed were associated with a migrant foundation that organized after-school recreational activities and academic support for the children, which they attended on weekdays. During COVID, the foundation had to shut its doors, and the children expressed distress at being unable to attend, to see their friends, and having to stay home.

3.3. Economic Difficulties

A common experience reported was the economic difficulties migrant families experienced during the pandemic. Many families migrated in search of better economic opportunities, having been unable to find them in their countries of origin. They arrived in Spain with few resources thus they lacked an economic cushion to lean on during the economic crisis brought on by COVID-19. The circumstances around Spain’s economy before the pandemic and the worsening situation due to the pandemic made their settling-in process difficult. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Have you ever had difficulty paying rent, electricity, or food?

“Yes, with this pandemic yes, before never. Since he worked for many years in this restaurant. Well, we paid the rent what we owe first, what’s left over we live with it. But in this pandemic, since sometimes they don’t charge, we were left like this with 3 kids, but thanks to (government services) they cover until we charged the month and then we can pay the rent. It’s very hard but thank God we are here really. This month has begun, a year and a half without work” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Some migrant parents reported losing their jobs due to the pandemic, and the circumstances around quarantine made looking for a job difficult when they weren’t allowed to leave their homes. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Has there ever been a time when you’ve been unable to pay for rent, electricity, or food?

“Yes, because my husband, almost a month and 17 days that he hasn’t worked, has passed, but this month he is working. Problem because he is not working, then we cannot pay want and eat that and, in the end, at least my husband has had some money has paid the rent, but we were…behind” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Migrants who did not lose their jobs completely reported their jobs were closed for the quarantine period or their hours were largely reduced. Although they were not fired, they were not working or getting paid either. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Has your family ever been unable to pay for rent or electricity?

“Yes, many times, when we came here, immediately after one month, my husband suffered from coronavirus. It was very difficult month for my family. It was only my husband who worked for the family. In March. It was very difficult for us to manage all the expenditures. We borrowed from friends, that is how we managed to pay the bills and the rent. But it was very difficult time” (Mother, Pakistan)

Additionally, testing positive for COVID-19 also resulted in a reduction of hours they could work as they had to quarantine. For some families, these periods were crucial to be able to feed their families and make ends meet. Every paid work hour counted. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

At some point, have you been unable to pay for rent, electricity, or food? Yes. Did you receive any aid?

“Not really, the pandemic and such, no, because so many people signed up, in the end it didn’t work out” (Mother, Bolivia, translated)

Due to the crisis in the overall population, many people applied for government aid and services, overwhelming the system unprepared for the size of the problem. Some people waited for months to receive aid, and some did not even try after hearing second-hand the stories of people who struggled to navigate the system and the bureaucratic obstacles, which will be further explored in the next section. One of the participants claimed:

“My mother in Bolivia is paralyzed half her body. It happened a year ago. It happened to her during the pandemic.”

The participant further responded to the following question as:

You haven’t been able to go see her since it happened?

“No, it’s impossible to travel with 4 tickets, too much money” (Mother, Bolivia, translated).

Economic difficulties kept many families separate even after the pandemic closures were lifted. Families were unable to reunite and take care of each other through sickness and health troubles, contributing to the theme mentioned above, as many of these experiences were interconnected.

3.4. Bureaucratic Obstacles

One of the common experiences that emerged for adult migrants was the struggle with application processes related to their visa status, work permits, and other paperwork that gave them access to resources such as education, health, a living space, or even food. There was no particular question in the interview guide regarding this subject. Yet participants brought up struggles of their own accord. For many parents, the process of filing for permits was delayed, with unknown timeframes around which they had no legal recourse other than waiting before they could work, and the pandemic extended normal timeframes. Some chose to wait if they had a spouse who could work in the meantime, others chose to work at irregular jobs while they waited to be able to get legal work. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Does your wife work?

“Not at the moment no. Because she now learns the language, after maybe. Now missing the card permits. I don’t know what the ministry now, you know they don’t receive the cards to work” (Father, Pakistan, translated).

Households with multiple adult members could depend on a second income to handle bureaucratic delays and job loss. Two-parent households migrated by first the father moving to Spain and then the mother joining him with their children once he had processed his visa and paperwork, they came over through Spanish family reunification policies. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Did you use any social aid services?

“Yes, but when we came here immediately there was no type of service available for us, because all the system was collapsing due to coronavirus, it was lockdown. When we came here, we don’t, there was different type of aid programs for the families. Initially we don’t understand what type of program and how to process them and how to apply for them. And when we spend time here, day by day we came to understand there are different type of program and get the support of the government. Initially we got support of food. In school and for family. After that we applied for income tax, they are paying familia numerosa. Numerous family members. We also applied for the rent habitatge but there is no response. We also applied for the social security seguridad renta minima a type of aid for the families with kids. A couple of weeks ago my husband told that it was rejected” (Mother, Pakistan)

Spain has developed many policies to help migrant families, including aid for large families with many children. During the pandemic, these policies were essential to make sure the children were able to eat, even if their parents could not work or had not yet found jobs. The efficiency of these systems is imperative. One of the participants claimed:

“There’s a lot of problems. And life is not more easy than what I thought. Well there’s a lot of rules too. Then is the COVID. You know there’s a lot of offices, that the appointments, very long times that can’t be met. For example, the IDs for my kids and my wife, that now almost 5 months past, that they don’t come, that I don’t receive the IDs, that they don’t process. For example, the numerous family. The ministry wants the physical IDs, not just the number, but now almost 5 months passed I don’t receive the IDs. That there are a lot of things that don’t happen in time as the family aid. Very stuck. That I work long hours to pay rent, to pay expenses, food. That life now as you know that, I think the life in Spain is better, but for now, I have a lot of problems” (Father, Pakistan, translated).

Some migrants reported that despite the bureaucratic delays, they recognized how their lives had improved; they still had more resources and opportunities than in their country of origin, and they speculated when the immediate crisis created by the pandemic subsided, they would see the fruit of their efforts. One of the participants responded to the following question as:

Have you received any aid?

“No. Because… I didn’t know how to ask, so I am waiting until I go to the social aid. I have the 2nd go social aid. I had the 30th of last month, but they said that she not there she has to get new appointment and now I have the 2nd. Of the following month. But apply me how I’m going to do with this card that I have for the sickness. But we are alright, thank God, if you have your health, you have everything. Yes, health is the most important” (Mother, Morocco, translated).

Despite the availability of resources, the system to request aid can be complicated, particularly for migrants who struggle with the language, as many Moroccan mothers reported they were unable to read or write, having received almost no education in their country of origin, they struggled to adapt in Spain where so many systems function through the written word and technology.

4. DISCUSSION

This research explored migrant families’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically the impact of circumjacent characteristics on this population. Using a qualitative research design, this study analyzed the interviews conducted with a child and a parent of each migrant family to explore the themes they reported about their lives during the time of the pandemic affecting their mental health. The key findings suggest social isolation, routine interruption, economic difficulties, and bureaucratic obstacles that ensued from public health restrictions had negative effects on their psychological well-being and can become risk factors to their mental

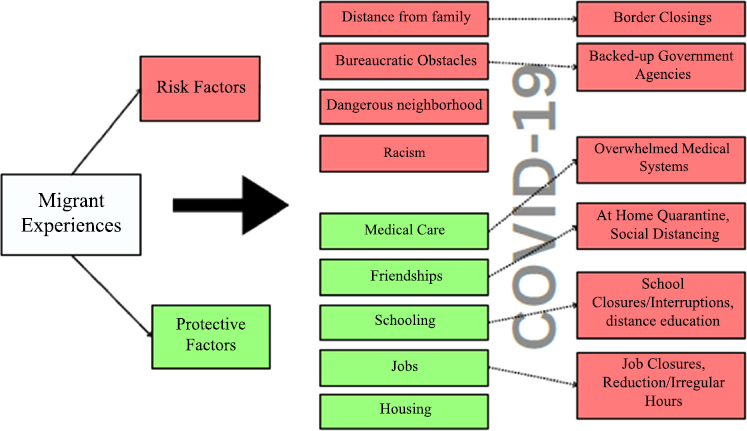

Summary of coded experiences modified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

health by increasing stress and removing or reducing access to social support systems. These circumstances were amplified for migrants due to their limited economic, social, and legal resources. These findings are concerning in consideration of the healthy development of migrant children because adverse psychological experiences and mental health problems in their parents are associated with an increase in mental health problems (Fig. 1) [34, 35].

Some of the protective factors offered by migrating to Spain were reduced or turned into risk factors for migrants’ well-being at the time of the pandemic and the following years. The experiences identified were interconnected, and their effects were felt by both parents and children in the family. Even if the initial experience belonged to the routine of one member, such as a parent’s job, the entire family was affected by the repercussions. Social support from common areas the families routinely spent time at, such as their school, job, or public spaces in the neighborhood, was temporarily interrupted and distanced. Economic challenges were multiplied by a reduction of available work hours by closures of multiple establishments or contagions by the workers. These two themes add to the interruption of the families’ routines and the rhythms they were familiar with, and they had to be flexible to adapt to in different ways during every stage of the pandemic. Finally, the government systems were slower and overwhelmed, creating increased bureaucratic obstacles, the access point to several resources such as economic aid and legal status.

4.1. Social Support

The purpose of this study was to identify how the experiences around migration may be risk factors for the mental health of this already vulnerable population in a difficult time, and social isolation was a recurring and highlighted theme by participants, a concerning result since loneliness is so damaging to people psychological [36]. Social isolation was distressing for both parents and children. The extended family was reported to be an important source of support that many migrant families lost access to. Additionally, friendships, which are of increased importance to migrants since they are so often separated from extended family by significant geographic distance, also had to be carried on from a distance, even if they were in the same neighborhood.

The social separation was caused due to health concerns, government mandates for national safety guidelines, and international border closures, as well as increased economic burdens and costs of travel. Some described keeping in touch with family through their phones. Finding ways of maintaining connection even with the quarantine of the pandemic and having to keep social distance or wait for borders to lift closures was important to people, and having the hope for the end in sight of being able to be with loved ones once again. Additionally, socialization in spaces such as school or work was lost, aside from interactions with friends and family. The overall loneliness of the experience was concerning for their mental health [36-39].

Children’s mental health has been identified to be significantly associated with the quality of the relationship with their primary caregivers [12, 35]. Isolation from other relationships limited children to the relationships they had with their family unit, particularly with their parents, whether this was a good relationship or a conflictive one.

Isolation had other negative consequences aside from the emotional distress of loneliness, such as limiting access to informal information channels during a time when understanding policy and medical procedures was crucial. For Moroccan women in the study who could not read or had limited understanding of the local language, depending on other people’s interpretation of the information disseminated by the news and the government was essential.

Additionally, migrants struggled to support their children’s remote education without the usual assistance from teachers or Ateneu staff, which negatively impacted academic success, and academic success in migrant children is important for their mental health and adaptation [37]. The role of social support from the staff of the Ateneu Foundation was quite important. In Belgium, studies of community centers during this pandemic underscored the importance of community-level mental health services that addressed social inequalities and cultural differences, especially for migrants. The findings emphasized the critical role of local services, highlighting their awareness of local needs, flexibility, holistic approaches, cultural sensitivity, and physical accessibility. However, the pandemic revealed challenges such as service overload, physical inaccessibility, and fragmentation, which hindered both users and providers [38]. These services require government support so they can continue to provide essential services in times of crisis. Overall, social isolation was an emotional, practical, academic, and economic complication for migrant families, and although technology can bridge some gaps, for vulnerable populations, there need to be other safety nets, such as community centers, to provide centralized aid and information.

4.2. Routines

Across several studies about mental health during the pandemic, the loss of routines emerged as a significant theme of distress, particularly for children and adolescents’ development, and confirmed in the responses of this sample. The loss of routines described by families included job loss, reduction of work hours, school closure, Ateneu Foundation closure, and mandates to stay indoors. This was reported to be distressing. Participants were impatiently waiting to reprise their valued routines, reunite with loved ones, rebuild financial stability, and continue their education.

Balanced routines were crucial for child development, including socialization, education, and recreation [9]. Children described how all of these aspects were reduced to their homes by doing school from home online, playing from home on their phones, and talking to their friends through social media. This was, however, not their preferred method, and they spoke of the day they would be able to return to their preferred forms of play outside in the park, swimming, playing football, and seeing their friends at school.

The establishment of new routines was difficult due to the changing mandates. Once quarantine was lifted, the families attempted to return to their previous routines with regular interruptions in the case of testing positive for COVID-19 again. This prolonged period of uncertainty, lasting many years even after the worst part of the pandemic had subsided, continues to be of concern for their mental health [8].

4.3. Economic Instability

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened these existing economic hardships, as many parents lost jobs or had their work hours reduced, leading to severe income reductions. The collapse of support systems during the pandemic left migrant families unable to access aid, even if they were familiar with navigating formal channels. In particular, access to basic needs, such as food and housing, became major issues. Some families managed to find relief through informal support from friends, landlords, and community groups. Despite the challenges, families stayed hopeful, viewing the difficulties as temporary and maintaining a positive outlook on their economic future, especially for their children.

Many migrants held low-wage, low-skill jobs that were especially vulnerable during the crisis [40]. Parents experienced job losses, unpaid work, reduced hours, and an inability to perform their jobs due to the risk of contagion, leading families to rely on external assistance to navigate the accompanying economic crisis. As mentioned above, social connections were limited and separated during the initial stages of the pandemic, leaving people cut off from these important sources of emotional and economic support. This experience during the pandemic was a concerning mental health factor as it related to the families’ ability to meet basic needs becoming unstable without clear safety nets such as extended family or efficient government systems.

4.4. Bureaucratic Processes

The pandemic significantly influenced migrants' post-migration adaptation by delaying the paperwork processes essential to their participation in life in Catalonia, affecting their legal paperwork applications, employment, access to affordable housing, and government aid to afford food. The psychological impact of the pandemic, particularly the long-term consequences of resource deprivation through inefficient systems, warrants further action to mend.

The pandemic also heightened reliance on technology by remanding multiple processes to online applications, necessitating digital literacy for communication with government agencies, families, and schools [41, 42]. However, language barriers hindered the ability of migrant families in this sample to navigate these processes, as they struggled with reading online content in the local language. The alternative support systems available during the pandemic were less effective for migrants than for the general population, forcing them to rely on the aid of strangers, friends, or organizations like the Ateneu.

The increased stress reported by families, particularly parents, regarding the delays in their ability to get ID cards to find a job or to get stipends for large families, ultimately boiled down to the necessity of feeding their children. Some families reported having to rely on external factors where the government systems failed them, such as irregular work or taking loans from landlords or friends. Temporary paperwork in times of crisis with streamlined processes can help avoid the vulnerability migrants are put in during wait periods while the more detailed and in-depth application is processed.

4.5. Limitations

The study faced several limitations, primarily due to a small sample size and challenges related to the recruitment of participants, which were compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. These limitations included time constraints that hindered in-depth interviews, language barriers, particularly with Chinese participants, and an imbalance in gender distribution among participants. Additionally, the study's findings were influenced by the unique characteristics of the sample, such as their residence in the marginalized Sant Roc neighborhood and their support from the Ateneu Foundation, which may limit the generalizability of the results to the wider migrant population but may indicate the factors impacting migrants settling into vulnerable neighborhoods which tend to be common points of entry. The research also encountered difficulties in thoroughly assessing the mental health of participants and in gathering comprehensive data on risk and protective factors for migrant families. Furthermore, the child participants’ young age restricted the depth of insights into their experiences. Despite these limitations, the study provided unique insights into the migrant experience during the pandemic, adding valuable, albeit context-specific, contributions to the field.

CONCLUSION

After COVID-19 began, it triggered mental health challenges due to restrictions, economic crisis, and the stress of the uncertainty of the time aside from the physical health issues that were at the center of the pandemic. The long-term impact is beginning to take shape and be understood. Although the pandemic may be coming to a close, it clarified the need for policies and systems that protect people’s mental health, particularly children, as other crises may arise in the future related to viruses or stemming from other issues threatening our times, such as climate change, which will highly impact migration [43].

The experiences described by migrant families as common and difficult bring into question the increased mental health risks from social isolation, economic difficulties, and bureaucratic obstacles. Additional support systems that have been put in place to help migrant families in the transition process of arrival were seen to be inefficient during the crisis of the pandemic when many government systems were overwhelmed. This is a warning to expand the capacities of our systems for the future. Protecting migrant children and adolescents’ psychological well-being during their development is of paramount importance, and this includes supporting their parents so they can support their children emotionally and practically.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATION

| HBSC | = Health Behavior in School-aged Children |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee on Animal and Human Experimentation from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain (CEEAH 5523).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Parents were interviewed first to sign their consent forms and those for their children. Their children were then interviewed and asked to sign an assent form.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.